How I Broke Production at Home (And Engineered My Way Out)

02/12/2025

There is a specific kind of silence that falls over a house when the DNS server goes down. I think of it like the calm before the storm. Netflix starts buffering, and then I hear a shout from the living room. “Abbas! What have you done to the internet again?!”

Last month, I learned the hard way why ‘pop it all on the same VM’ is a strategy that has a strict expiration date. I was running everything; my ad blocker, reverse proxy, spell checker, via docker compose on a single Debian VM. It was efficient and quite easy to reason about. Until tried to resize the storage to make space for some more services.

Something that should have been routine, but I corrupted the partition and broke the VM connecting me to civilisation.

Why I Put It All in One Basket

I’m a big proponent of containerising applications. Anyone who has multiple services will agree that containerisation makes it easy to run a lot on a single machine: clean isolation, simple deployment, quick iteration.

I like to experiment with all sorts of services—Kubernetes deployments, self‑hosted LLMs, random tools—but I had a belief that my load‑bearing services (the ones I actually rely on every day) should be kept as simple as possible.

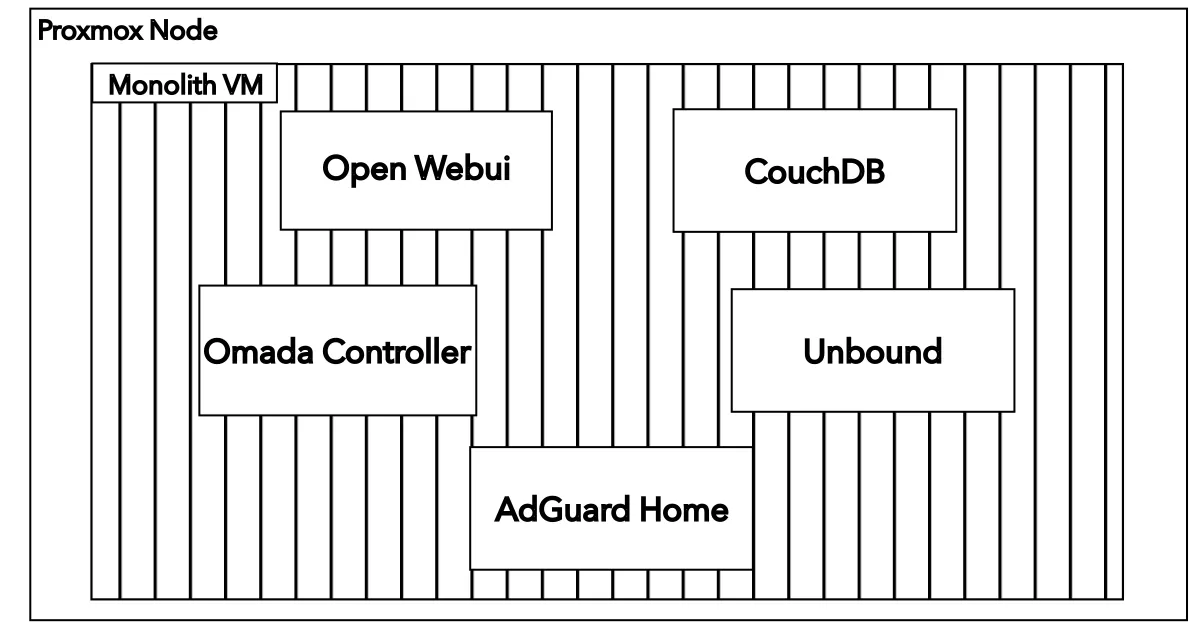

Proxmox is the backbone of my home lab, and Docker is something I use daily at work. So the plan felt obvious:

- Create a dead‑simple Debian VM in Proxmox

- Install Docker

- Run everything with docker‑compose

That’s exactly what I did. On that one VM I was running:

- open‑webui – for experimenting with local/remote LLMs

- adguard‑home – ad blocking and DNS

- unbound – recursive DNS resolution

- withings‑sync – syncing my Withings device data to Garmin

- glance – monitoring

- LanguageTool – spell/grammar checking

- couchdb – storing and syncing my Obsidian notes

- Omada controller – configuring and controlling my home network

It was a tidy, efficient little monolith. Until it wasn’t.

1

1

The Crash

The incident started as a routine maintenance task. I wanted to deploy a new service, but the VM was running low on space. In a cloud environment like GCP, expanding a root disk is trivial. In my specific Proxmox + Debian setup however, whether it was a miscalculation or a typo is almost irrelevant; the real problem was that the system’s architecture made a simple human error catastrophic.

The resize operation failed, the partition got corrupted. The VM stopped responding. A reboot didn’t help; it refused to start.

And this is where the architectural flaw of the ‘Monolithic Homelab’ revealed itself in the worst possible way.

Because AdGuard (my DNS server) and Unbound (my DNS resolver) were trapped inside that corrupted VM, my home network lost the ability to resolve DNS. I didn’t just lose my server, I lost the ability to Kagi (hope this sticks) how to fix my server.

The Omada controller, which configures the router, was also running in this same VM. This meant that I was unable to change my gateway settings to temporarily point to Cloudflare for DNS resolution.

Staring at the blinking cursor in my terminal and the “Network is unreachable” error message, I realised that my “efficient” single-VM strategy had created a massive single point of failure.

Now you might be thinking, why not just spin up a new VM, git pull, docker compose up, tweak some config and move on.

But I hadn’t committed the config in a while, neither had I done any back-ups.

Murphy’s Law was very much dealing with me.

The Copper Lining: Enter System Rescue

I could not boot the OS, but I knew the data, the up-to-date Docker compose files, and the persistent volumes were likely still intact on the disk.

I needed a way to harvest the patients organs. Respectfully.

I’m not a stranger to rescue images. At Autometry, I’d used gce-rescue more than once to save VMs on GCP with similar issues.

Luckily, there is a similar tool outside GCP: System Rescue, a Linux system on a bootable ISO designed for exactly this kind of nightmare.

- Mounting the image: I uploaded the System Rescue ISO to Proxmox, attached it to the corrupted VM’s CD/DVD drive, and changed the boot order so that the VM to booted into the rescue environment.

- Mounting the Disk: Once inside the shell, I used

lsblkto identify the partition. I created a temporary mount point (/mnt/vmroot) and mounted the corrupted disk. - Exfiltration: The file system was accessible. I could see my service files in

/home/apps, where I kept them.

From there, I spun up a new temporary, lightweight VM, which I called coredns. Using scp (Secure Copy Protocol), I surgically extracted the critical data from the rescue shell to the new machine.

scp -r /mnt/vmroot/home/apps/update_projects.sh \

core@192.168.0.xx:/srv/appsWithin minutes, I had the data out. I installed docker on the new VM, ran docker compose up for just AdGuard+Unbound+Omada Controller, and not long after, the house was reconnected to civilisation.

The Lesson: Cattle, Not Pets

This outage forced a hard pivot in my engineering philosophy.

I had treated my homelab like a pet: a single, cherished server to be nursed and maintained. When it got sick, everything ground to a halt.

This reinforced a core engineering truth:

Resilience is not a feature you add later; it is a constraint you design for. The blast radius of a failure should never exceed the scope of the change being made.

I am now moving toward a cattle approach, prioritising distribution and redundancy.

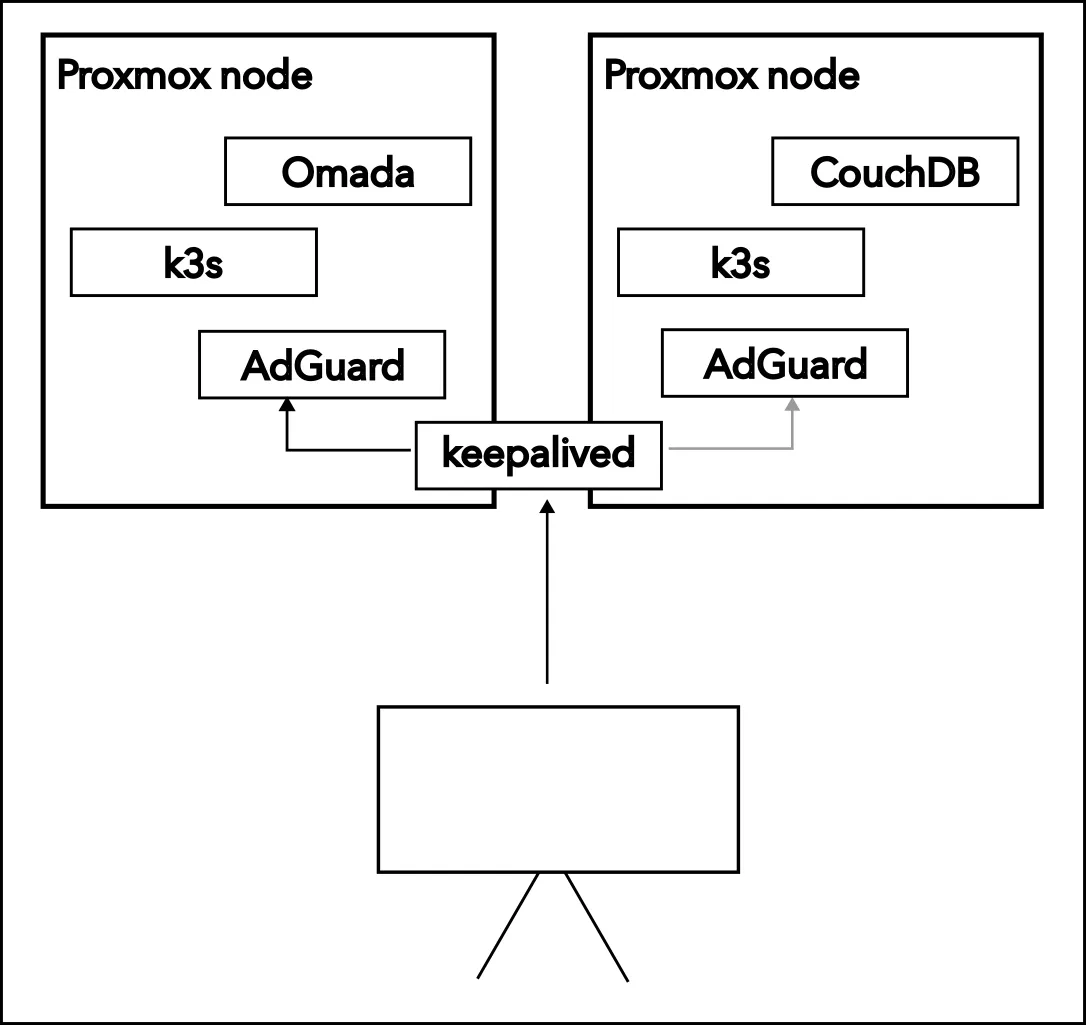

- Decoupling the Management Plane: Critical network infrastructure (DNS, Reverse Proxy, Omada controller) should never run on the same substrate as experimental application workloads or less critical tools. I moved DNS to lightweight, separate LXC containers.

- High Availability: I implemented

keepalived, a service that puts a single virtual IP address in front of multiple IPs and routes requests to the service that is available. In addition to this, I spun up two DNS containers that are always running on separate nodes in my proxmox cluster.keepalivedroutes to the other one if one goes down. - Kubernetes: While docker compose is excellent for simplicity, the incident accelerated my adoption of Kubernetes beyond experimentation. Kubernetes naturally handles the concept of “desired state” and self-healing, ensuring that a single node failure doesn’t take down the entire cluster.

2

2

The tidy monolith was nice till it wasn’t. The new philosophy is simple. No simple maintenance task should ever be able to take my entire house offline again.